By Jakob Engblom, Intel System Architecture and Simulation

George Bernhard Shaw once said that “Those who can, do. Those who can’t, teach.” Some funny people then added “Those who can’t teach, consult.” I do not agree with this.

Shaw’s comment is fundamentally unfair to teachers: teaching is hard. It is often harder to teach something than to do it and being forced to teach or explain something often leads to a deeper understanding.

The physicist Richard Feynman had a better understanding of teaching (in my opinion). He is supposed to have said that “You do not truly understand something unless you can explain it to a college freshman.” That is a very high bar, and he admitted that there are some things in the world we just do not understand well enough to pull that off!

Teaching Forces Understanding

I am on Feynman’s side. I have spent a significant part of my work in the past few years building Simics® training materials, teaching Simics users, and coaching other Simics trainers. In the process, it is clear that explaining something to someone forces you to build a deeper understanding of it. Until you have taught another person about something, you probably have not really understood it in its full depth.

Another biproduct of developing training is that I have found many small inconsistencies and odd behaviors in the product. That validates another classic product management insight: developing documentation and training materials is an essential part of producing a quality product.

Developing training is a good high-level product test: it forces the developer or the expert developing the training to look at the software from the perspective of a novice user. In particular, working through longer exercises, where multiple features are involved, exposes inconsistencies and missing features —issues that never appeared when looking only at a single feature or use case in isolation.

In my experience, it is actually easier to do something or use something than to teach other people to do it or use it. You can do things without necessarily understanding exactly what is going on, just by looking at examples and trying stuff until it works. It’s a lot like the infamous C idiom of “permutation programming” where you randomly change around the stars and arrows of pointer expressions until you get something that compiles. The result works, but can you explain it to someone else?

Realizing Inconsistencies

The Simics product is very powerful, with many features that have been added, updated and removed through its more than 22-year life. Inconsistencies are to be expected after such a long history of design decisions by many individual developers. Each command or feature makes sense in its design when considered on its own, but it might not quite look like other similar features when taking a global view.

I would claim that most users adapt to such inconsistencies, at the cost of a higher cognitive effort and more looking into documentation and examples to figure out the peculiarities of a particular program feature. Many users are happy enough if they can get something to work at all—without reflecting on the elegance, logic, conciseness, or robustness of the resulting solution (I recommend this little reddit post for what that can look like). But when building hands-on labs and working through examples, inconsistencies become more visible. Writing down commands and the output from commands, and taking screenshots of the GUI and explaining what they show, forces a consideration of precisely what is going on. Suddenly, it becomes painfully apparent that some commands use “-r” to mean “recurse through sub-objects” while others use it to mean “read operation”, for example.

Reconsidering Old Standards

Developing training content also made me to revisit some old, standard commands that have been parts of Simics software for a very long time. Once upon a time, their design made sense. However, the virtual platform designs change over time. In particular, the scale and size of platforms and configurations have increased tremendously. Back in the early days of Simics, a model of a high-end server would contain a hundred objects. Today, a server platform would tend towards 40,000 objects and millions of distinct programming registers.

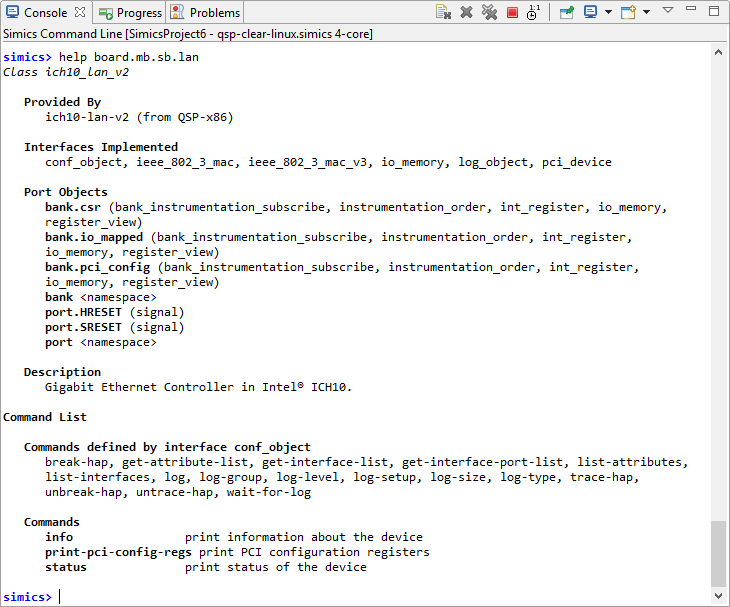

Figure 1: The Simics help command applied to a LAN model

The new scale and size have implications for commands that inspected the configuration. For example, applying the Simics help command to an object in the configuration as shown in Figure 1 prints the most important information first, which makes intuitive sense. However, the command also used to print all the Simics attributes of the object at the end of the output. This was fine when an object had maybe a dozen attributes. Today, they routinely have thousands if not hundreds of thousands of attributes.

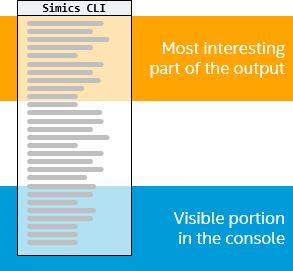

That led to the problem shown in Figure 2: the interesting part of the output gets scrolled far off the screen by an avalanche of less useful stuff. This kind of problem becomes obvious when you copy-paste the output into a lab document, and you have to write something like “Scroll back up to the start of the output to see…”. At that point, it is time to stop and file an enhancement request to fix the behavior, rather than trying to explain it or work around it in the labs.

Figure 2: Hiding the interesting output with too much irrelevant output

Requesting Enhancements

Enhancement requests, issues, bugs, stories—whatever you call them, training development produces quite a few. Going into our JIRA system and checking the statistics for the past six months, it turned out that I had filed more than 100 stories and bugs with findings from the training development. Some of these are small, some are big, but the number overall is an indication of how effective training development is as a test strategy.

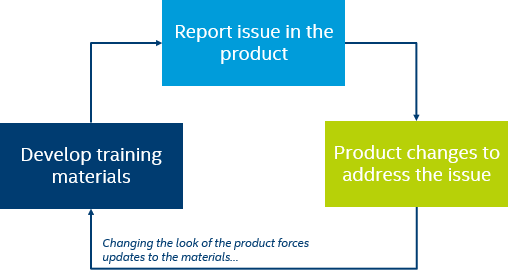

Figure 3: The feedback loop from training development to product changes

However, no good deed goes unpunished. Once the reported issues are fixed and the product updated, it is necessary to revisit the training materials and make sure they correspond to the updated behavior or output. This can be a bit annoying since it forces a rework of existing materials and a new release of the training package… But in reality it is mostly a benefit since it effectively tests the updated product. Does the functionality actually make more sense after the update? Was something missed in the initial issue report?

Rolling into Agile

From the perspective of Agile development practices, training development is a natural fit. The issues discovered during training development feeds into the backlog. Once a feature has been implemented, the training development serves as an acceptance test and feedback mechanism for the results. When developed close to the software development teams and with the right to add issues to the backlog, training becomes tightly integrated with the development of the product itself, rather than something done post-facto and outside the product process.

Promoting User Empathy

On the topic of developers and training, I find it very useful to have developers serve as teachers. It is a great way to come in contact with users, and to discover and experience aspects of the product that they might not otherwise use or interact with. A developer is not necessarily a user of a product and might not have the same perspective on it as a regular user. Teaching a training session builds empathy with users and a more intuitive feel for the problems that users have with the product.

Summary

For any complex piece of software, training is a necessary part of the complete product offering. The development of the training content provides a great opportunity to test the product functionality and look-and-feel, leading to the discovery of inconsistencies, oddities and missing features. As we have developed new generations of Simics training and updated existing training, we have also driven improvements to the product—both for single features and across the product as a whole. Training should be developed close to the product development teams, in order to facilitate the feedback loop from training into the product, and also to let developers work on delivering the training as a way to learn more about their product.