Amazing demos abound at computing conferences, but one in particular stood out for fans of Intel® processors at the 2019 COMPUTEX Taipei* show: Rense de Boer’s Forest Views. The short demo showcased the power and performance of the 11th generation of Intel® Processor Graphics Architecture, commonly referred to by the pre-launch codename Ice Lake hardware.

De Boer’s photo-realistic, real-time rendering of complex forest scenery was enabled by early hardware provided by Bobby Oh, strategic business development manager for gaming-developer relations at Intel. Oh said de Boer’s work shows how “game developers can take advantage of the new features to push the boundaries of what’s possible using processor graphics.”

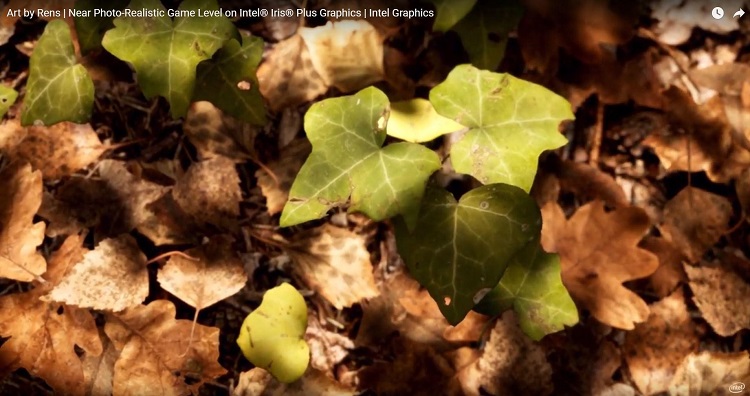

Forest Views capitalized on variable rate shading (VRS), a new feature on Intel® Core™ CPUs. “VRS is a fine-grained shading control that allows us to tune pixel shading resources to where they’ll have the most visual impact, saving significant frame time,” said Kelly Gawne, game performance engineer at Intel. “It’s been a privilege to work with Rense in bringing his artistic vision to a whole new platform,” she added.

A self-taught 3D artist, de Boer has, since 2003, honed his skills working at studios such as DICE* and completing contract work for Epic Games*. He is known for his work on the Battlefield* franchise, specializing in stunningly realistic graphics. And, throughout his career, he has striven to close the gap between offline, pre-rendered cinematics and their real-time equivalents.

We talked to de Boer – of Stockholm, Sweden – about his background, his new project, and his work with the new Intel graphics hardware.

From Playing Games to Making Games

De Boer played a lot of computer games when he was growing up, and has fond memories of two in particular: Final Fantasy* IX and The Legend of Dragoon*. Both were role-playing games with high immersion and excellent graphics.

“The vast world you could explore, and be a part of, left a big impression,” he recalls. And when the classic Halo* debuted, he was completely hooked.

However, he notes, “We played a lot of games, but we really didn’t know anything about how they were built.” In those days, the resources available to developers were limited. Fortunately, a friend had begun learning to code, and was familiar with game engines and 3D software. De Boer was introduced to 3D and found he had a passion for it. “It was soon clear,” he says, “that I wanted to make 3D art my career.”

His first big studio job was in 2011, working at DICE on Battlefield 3. Eager to understand the processes behind good-looking and optimized games, he moved from 3D work to building environments, then technical art direction.

Figure 1. Battlefield* 3: Aftermath, on which Rense de Boer played a key role (Image courtesy of DICE*)

Battlefield 3: Aftermath (2012) is by far his favorite, because his contributions had, by then, grown in importance. He took on technical art direction and learned to push quality, make decisions, and lead a team. “We managed to work so close, like a well-oiled machine,” he recalls with pride. “We really achieved and delivered something unique.”

In the trenches every day, working for a major studio, de Boer never collected degrees or studied at a university. “Everything I learned before starting in the industry came from online communities like Polycount*”, he says. He followed online tutorials and spent hours bouncing ideas off fellow artists. To date, he’s been a part of 15 different titles and over 40 levels. He now runs his own company, focused on advancing real-time graphics and developing a full-size exploration game. “I am the only developer on it,” he explains, “so I take on just about every role you can imagine.”

De Boer conducts research and development on code, animation, audio, gameplay, and any areas where he identifies gaps in his expertise. He already has fans anxious to see the game he’s working on. “Hopefully,” he says, “I will soon be able to show off my project.”

A Deeper Dive on Photo-Realism

As new tools open new opportunities for photo-realism, de Boer works hard to keep pace. “Anything you want to be good at takes an extreme amount of practice,” he observes. “It means questioning everything you know and figuring out what it takes to achieve your goal.”

Figure 2. The Forest Views demo features shadowed ivy on a forest floor, in stunning detail. (Image from the Forest Views demo, courtesy of Rense de Boer)

For years, de Boer worked around the clock creating art, capturing content, and building forest environments. Early on, the next step wasn’t always clear. He would update his hardware, then update the software to take advantage of that hardware. He would upgrade his camera and the lighting rig that he built to capture plant images. “It all comes down,” he suggests, “to finding a good balance between studying nature, aiming for next-generation hardware, keeping up with the current tools, and figuring out how they can give better results or speed up your workflow.”

He was happy with the results he was getting as he progressed systematically through engine setups, hardware upgrades, new features, and improved images. Occasionally, however, something would come along that caused him to reevaluate everything. In 2019, it was the chance to use new Intel® hardware.

“I had conversations with Intel’s Bobby Oh for quite a while, and we were looking for an opportunity to work together,” de Boer notes. With the Ice Lake launch approaching, Oh suggested teaming up on a demo to show off the system’s new 11th generation graphics capabilities, including VRS. Oh provided the new hardware, and encouraged de Boer to use its features to optimize his work.

Kelly Gawne, says de Boer, “worked extremely hard” to implement his photo-realism project in Unreal Engine*. He chose Unreal because he believes it is the most powerful engine available, and he is very comfortable with its workflows. “The features, blueprints and documentation, and excellent support, make it possible for a single person or small team to hit a whole new level of discipline, technique, and artistry” de Boer said.

As with any new system, there was a lot to learn when the Intel hardware arrived. Customarily, de Boer runs tests to see how new systems respond. The tests allow him to calculate what he calls the “base cost” of a simple scene. Depending where he is in development, the base scene will contain approximately 100 simple or complex meshes. It also includes components such as directional light, sky light, post-processing volume, and fog.

The next step is to look at the performance. Once he identifies bottlenecks and establishes the duration of each pass with different settings, de Boer can begin to get a good understanding of the available performance.

Intel® Tools Help Optimization and Experimentation

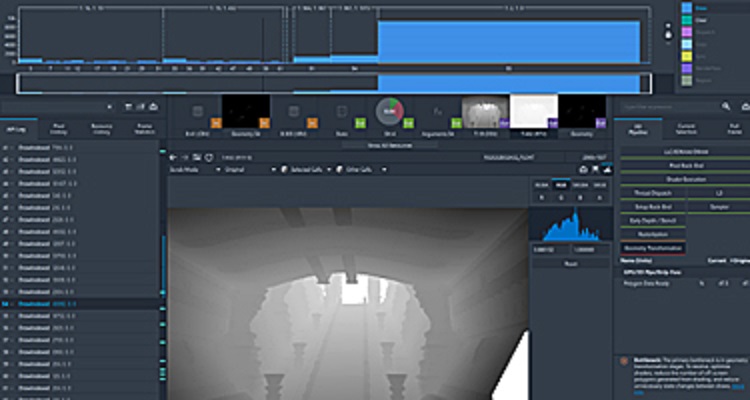

Intel® Graphics Performance Analyzers (Intel® GPA) helped improve the performance of de Boer’s graphics-intensive Microsoft DirectX*12 application. With Gawne’s help, he used Intel GPA to profile multiple content and rendering passes. “It was a pleasant surprise to see how easy it was to use,” says de Boer, “and to find all the data relevant to me.”

Figure 3. Intel® GPA tools helped de Boer optimize for frame rate and identify bottlenecks.

Among the biggest challenges were finding a balance between file size and performance, and lighting the scenes. "You can have great content," de Boer says, "but, if the lighting is not in place properly, everything will look wrong."

With these budgets in mind, de Boer typically begins his balancing act. The level design dictates how much needs to be rendered at once and how dense the environment can be. The size of the playable area, the viewing distance and the theme all play a major role. He tests different layouts, experiments with culling effectiveness, and inspects content density.

Having established a geometry budget, de Boer builds content within strict parameters. VRS enables denser meshes up close and faster level of detail steps, so de Boer next balances engine settings and disables different rendering passes to win back performance.

In Forest Views, the meshes had low polycounts, so de Boer had to use more texture memory to maintain high quality. He assigned 4K textures to ensure the models looked detailed and held up under close inspection.

To run the project on integrated graphics, de Boer stripped the engine, using Intel GPA, to determine the duration of different rendering passes. The prepass had little effect, so he disabled it by turning off the DBuffer.

He also disabled the depth of field (DOF) pass, which was very costly even at low settings. When Intel GPA revealed that the DOF recombine remained active and took up to 0.5 milliseconds, he eradicated it entirely with the r.separatetranslucency command.

Other passes were more straightforward. Fog, for example, added little visual quality to the forest environment, so he took it out.

The team also determined that ambient occlusion could be baked into the lighting. The performance saved was spent on adding content to the scene.

To avoid incorrect performance readings, de Boer used r.shadow.unbuiltpreviewingame. This command mitigated the high rendering cost of preview shadows associated with the scene’s unbaked objects.

Figure 4. Shadows in Forest Views. (Image from the Forest Views demo, courtesy of Rense de Boer)

As Forest Views demonstrates, de Boer expertly deploys shadows across terrain and foliage. Performance, he says, is the real driver: “When you pay a small rendering cost to cast a shadow, you want to ensure that it is used to its full potential. By covering parts of the ground in shadow, you create an opportunity to turn off some of the other shadows, which in turn gives you that cost back.” The dynamic movement of the shadows brings the scene alive. They also provide a powerful tool for contrast, and guide the player through the level.

After completing the level design, de Boer locked in the location of the sun, which allowed him to utilize one of his specialities: placing content in interesting areas where sunlight breaks through to illuminate the terrain.

“I have been developing nature scenes for a long time,” he observes. The passion shows, and the joy of Forest Views was in maximizing his talents with the new Intel hardware. “To really put Ice Lake and my skill set to the test,” he explains, “I wanted to develop an amazing demo that showcased a playable environment running on integrated graphics. I’m very happy with the results.”

11th Generation Intel Graphics Pass the Test

De Boer was very impressed with the performance available on a system that doesn’t use high-end, discrete graphics cards. “Developing for integrated graphics was not very different from any other platform,” he says. “To get roughly the performance of an Xbox One* out of a processor whose main function is for something else is truly amazing.”

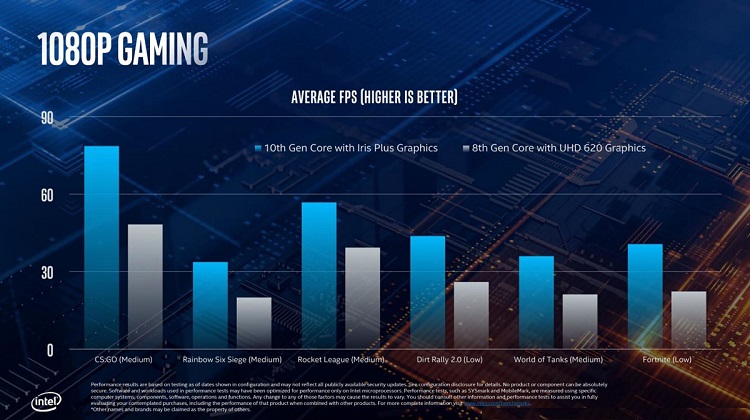

Figure 5. The 10th generation core with Intel® Iris® Plus graphics hardware offers performance boosts across the board.

For de Boer, the 10th generation core with Intel® Iris® Plus graphics hardware represents an excellent step forward: “If you develop or play a lot of console games, Ice Lake is a great platform to add. And, with its all-around strength, it is a fantastic workstation at home, in the office, or on your travels.”

The field is fast evolving, so he is optimistic that he’ll continue to see opportunities for more experimentation in forthcoming release cycles. “Software and hardware have made huge leaps these past few years,” he notes, “and now even real-time ray tracing is possible.”

Figure 6. De Boer has a talent for photo-realistic rocks and terrain, but has to balance lighting and shadow to hit a playable frame rate. (Image from the Forest Views demo, courtesy of Rense de Boer)

Lighting plays a major role in visual quality and can now, finally, be resolved with real-time ray tracing. It allows for accurate soft shadowing plus ambient occlusion and reflections, which previously held back the sense of realism.

Experience in the industry has taught de Boer that nothing is predictable. Yet he is optimistic that, within a few GPU generations, gamers will enjoy the same visual quality as moviegoers. Beyond additional content, denser meshes and higher resolution textures, he sees opportunities to build worlds whose complexity would have been unimaginable until very recently. These will require fresh workflows, expanded imagination, and new skill sets, but real-time cinematic quality is getting closer.

“With more processing power available,” he suggests, “the next few years will be less focused on compromise, due to performance or lack of features, and more on accurate simulation and representation. That’s going to be huge: to see what is unlocked.”

De Boer is excited to see Intel move into the GPU market. “What I would love to see are new discrete GPUs,” he says. “This would be a perfect match for my work, as it is all about pushing quality and exploring opportunities.”